What is Science Fiction?

(Note: For many years I taught a course called “Science and Science Fiction.” This is one of a series of essays based upon my lectures.)

Categorization is a basic task. Years ago, we owned beagles who had a keen sense of categories. They would eagerly chase after ground-dwelling animals of all sorts: rabbits, squirrels, lizards; but birds of all kinds they ignored, even if said bird had its wings folded and was strutting on the ground. We’re not bird dogs was a discerning instinct bred into them.

We separate fiction into categories, or genres, as well: romance, mystery, historical, and of course science fiction and fantasy. Such categorization is useful as we may prefer romance over science fiction, or fantasy over mystery.

But the mechanism of categorization can be puzzling. Perhaps our dogs quickly counted legs, although I doubt it. More to the point: how do we delineate what is and is not science fiction?

The Oxford English dictionary defines science fiction as “imaginative fiction based on postulated scientific discoveries or spectacular environmental changes, freq. set in the future or on other planets and involving space or time travel.” The science fiction author and editor Ben Bova said science fiction was stories “in which some aspect of future science or high technology is so integral to the story that, if you take away the science or technology, the story collapses.” My American Heritage dictionary: “Fiction in which scientific discoveries and developments form an element of plot or background; especially, a work of fiction based on prediction of future scientific possibilities.”

These prescriptive definitions indeed circle what we recognize as science fiction. Yet it is not hard to find examples that feel like science fiction, but formally not satisfying those definitions.

Two thought-provoking examples are Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, an alternate history where the Axis powers have won World War II, and Margaret Atwood’s dystopian The Handmaid’s Tale (and its sequel, The Testaments), in which the US has become a theocracy. Many people would recognize them as science fiction, yet they have none of the elements in the definitions given above. In fact, Margaret Atwood famously dismissed science fiction as “talking squids in space,” in part to exclude The Handmaid’s Tale as a science fiction tale.

This problem of categorization is not limited to science fiction. Consider games. Games can range from children’s pattycakes to professional football. Trying to encompass both leads to

complicated and convoluted definitions. One could exclude pattycakes, but such a choice feels motivated more by pedantry than by our experience of games.

While one could exclude those novels on the prescriptive basis of not fitting a rigid definition, I prefer to take a descriptive approach and try to understand why, despite the lack of science, do readers think of The Man in the High Castle and The Handmaid’s Tale as science fiction?

Rather than a definition, we can follow Wittgenstein and define a genre as a bundle of tropes. ‘Trope’ is a fancy literary term, meaning some situation, image, or other idea that occurs frequently—but, crucially, not necessarily always—in members of a given genre.

So, for example, orphans, cruel adults, and friendly animals are common tropes in children’s literature. Hard-bitten or eccentric detectives are common tropes in mysteries, as are the motivating death of a partner. Fantasy tropes include magic, hidden lands, friendly animals (again), secret abilities, and so on. Finally, common science fiction tropes include space travel, time travel, robots, the future, space travel and aliens, biological manipulation, and so on.

Conceiving of genres as bundles of tropes better describes the wide variety of members of a genre. Two science fiction stories can have non-overlapping tropes. It’s possible to have a science fiction story set today, but with a key scientific advance, or a story set in the far future but without a focus on specific science.

Even if we abandon rigid definitions for bundles of tropes, those bundles need not be arbitrary. We can still ask if there is some underlying theme to a genre. We can also ask how it is we discern the difference between science fiction and fantasy.

As a first step, consider the thoughts of scholar James Gunn (not the movie director). Gunn focused on the role of change. He classified traditional literature as the literature of continuity, fantasy as the literature of difference, and science fiction as the literature of change. Specifically, fantasy, such as the Lord of the Rings or Harry Potter, “occurs in a world not congruent with ours or … incongruent in some significant way.” Even though Tolkien wrote his stories of Middle-Earth as a mythic prehistory of Europe, no one, not even Tolkien himself, thought one should take it as literal history. And, I’m sorry to say, you are never going to have an owl deliver to you an invitation to attend Hogwarts.

In contrast, Gunn claimed that in science fiction, “some significant element of the situation is different from the world with which we are familiar, and the characters cannot respond...in customary ways...a changed situation requires analysis and a different response.”

Indeed, as I’ll write about in a future essay, science fiction explicitly invites the reader to ask how the situation changed. In contrast, fantasy seldom invites the reader to ask how magic came into the world (although Larry Niven’s novel The Magic Goes Away addresses the reverse: a world full of magic that is fading and becoming our non-magical world).

Science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson has sharpened Gunn’s approach in a way I find particularly satisfying. (I should acknowledge I took several courses from Robinson in college and consider him a mentor in science fiction literature and writing.) Robinson calls science fiction “the histories we cannot know.” Mainstream literature is factually possible and plausible: we can imagine these characters and situations existing in our world. Fantasy is counterfactual and historically disconnected from our world: there is no way to get there from here. It is also scientifically disconnected: fantasy requires a change of history and of physics. Science fiction is counterfactual but nonetheless historically plausible: if either future or past history were different, we could have a particular science fiction scenario.

This description beautifully encompasses both alternate histories such as The Man in the High Castle and future histories such as The Handmaid’s Tale. Indeed, typically alternate histories signal when and how history has altered; in the case of The Man in the High Castle, a conversation lets us know that Franklin Delano Roosevelt was assassinated, changing the course of World War II.

Why then call it science fiction? Especially when some classic science fiction texts like those mentioned above have little to no science in them?

The reason is the role science plays in science fiction. Science fiction is not about predicting the future. It is not even about discussing scientific realities or possibilities. No, science fiction is the literature of change; and science, as well as technology, is a clear driver and marker of change. If a story involves a school for wizards, it is about a world different and ultimately disconnected from ours. If a story involves flying cars, it is about a world changed from ours. The earliest science fiction stories, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to the novels of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, to the pulp stories of the 1920s, all focused on scientific and technological change and challenges. But as the genre of science fiction expanded, the stories extended beyond the boundaries of scientific change to more general explorations of the dynamism of history.

Science fiction never lets us forget that history happens. The world could be different… no, the world will be different, be it in positive or in terrifying ways. By its very nature science fiction invites us to think about how those changes could occur; it is intrinsically subversive. The first interracial kiss on American television occurred in Star Trek, although, sadly, under force by an alien psyche; the studio was so fearful of blowback they ordered a version of the episode without the kiss, and it was because William Shatner deliberately ruined those alternate takes that the kiss was aired. Martin Luther King Jr. told Nichelle Nichols, who played Lt. Uhuru in the original series, that Star Trek was one of the few TV shows he and his wife allowed their daughters to watch, because it had a Black woman on the bridge of the starship.

Conversely, fantasy tends to be nostalgic and looks to the past, especially high fantasy with its European medieval trappings. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings is one long grieving for a lost world, rooted in the deaths of his parents at an early age and of his friends in the trenches of World War I. Rowling’s Harry Potter series likewise is arguably about the loss of childhood innocence. There’s a reason many fantasy series are about children traveling to magical lands: they grieve the loss of the magic of childhood.

(Of course, not all fantasy is nostalgic. Some fantasies truly do imagine historical change. Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials envisages the overthrow of heaven itself and the death of God. R. F. Kuang’s novel Babel is a searing indictment of how colonialism literally eats itself alive and, like Pullman, describes a revolution casting down the oppressive magical system. As I’ll write in a future essay, once boundaries are established there will always be some who test them.)

Science fiction itself is changing. The rise of cheap computer-generated images, streaming services hunger for content, and the relative ease of self-publishing today, means there is more science fiction content than ever, which in turns leads to science fiction bleeding into other genres. Science fiction is no longer a literary outcast. And that is not a bad thing.

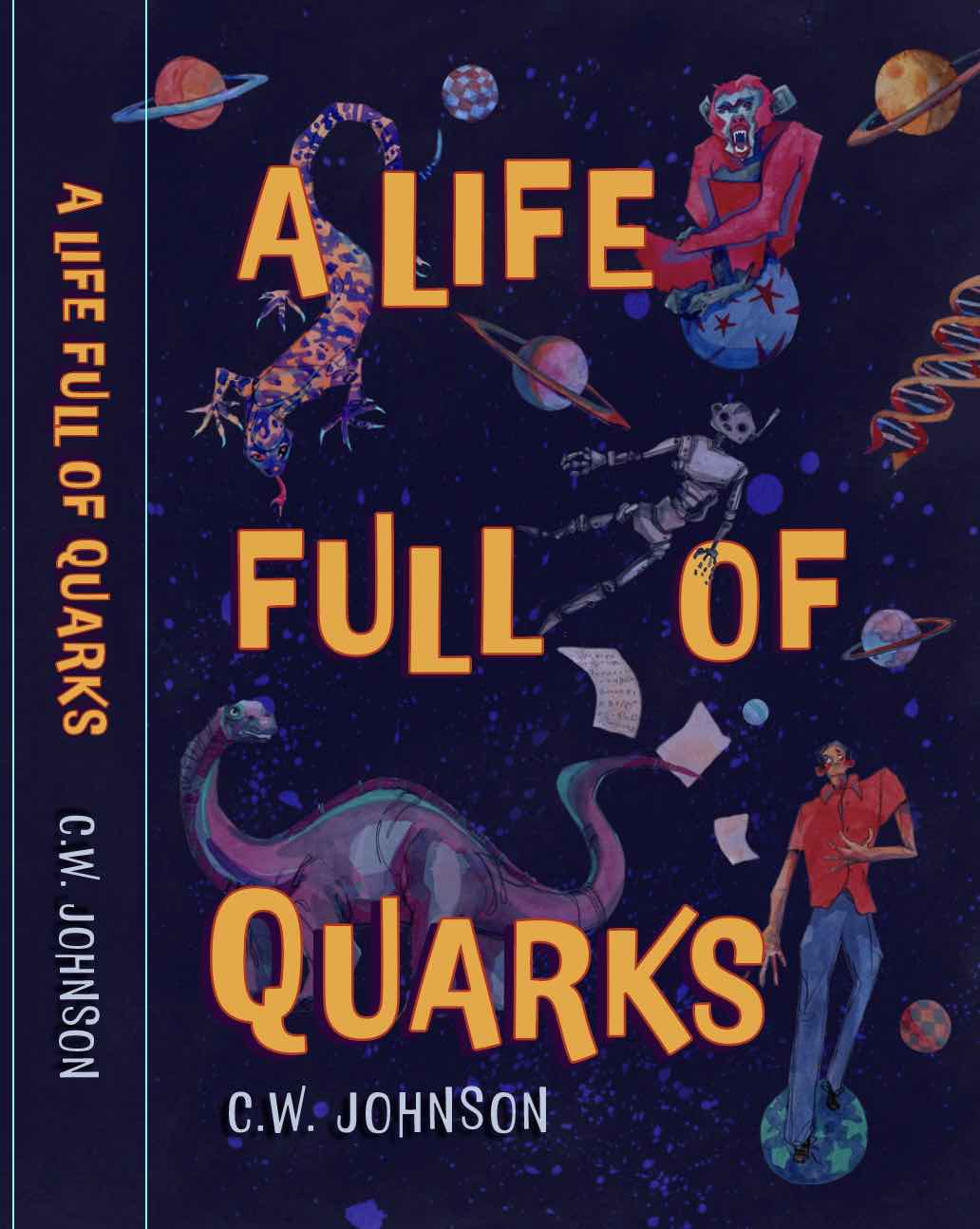

As a final note, let me comment on magical realism, if only because my novel is arguably closer to magical realism than to either strict science fiction or fantasy. Magical realist texts tend to occur in what is recognizably our mundane world, but with fantastical or unrealistic elements seeping into the story like pieces of a dream.

It is that dream-like quality that distinguishes magical realism. Science fiction, of course, would have you believe it is as rigorous and logical as science itself, and fantasy assumes that magic, no matter how weird or wild, nonetheless has rules that one can follow and master; why else go to a school for magic?

Magical realism instead tends to focus on the absurdities and incongruences of life, and questions whether life or history has rules. Science fiction often views history through the lens of the personal: in Frank Herbert’s Dune, through genetic breeding programs and drugs Paul Atreides becomes a prophet and messiah, and the spark of interstellar war. Magical realism inverts this, seeing the personal through history: in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, Saleem and all the children born at the same time as the newly emancipated country of India are given (like the country) great gifts, but those gifts come to haunt Saleem (just as India struggle to meet its own promise). To put it another way, science fiction uses the personal as an excuse to talk about Big Ideas, while magical realism uses Big Ideas as an excuse to talk about the personal.

Because of the dreamlike quality of magical realism, it is much harder to pull off than science fiction or fantasy. You’ll have to decide for yourself if I succeeded in A Life Full of Quarks.