Deconstructing the Iliad

I only recently read Homer’s Iliad in full. Like many people, as a child I became fascinated by Greek and Roman stories of gods, heroes, and monsters. But the translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey I picked up were so awkward and off-putting I quickly lost patience and put them aside.

A few years ago, my wife and I bought the new translation by Emily Wilson of the Odyssey, and over the course of many nights read it aloud to each other. (Early in our marriage we picked up the habit of reaching aloud to each other in the evenings, and keep an eye out for suitable texts.) More recently Wilson has translated the Iliad, and I decided to finally read it—though silently, to myself.

You may be familiar with the broad strokes of the story. The Greeks have already laid siege to Troy for ten years, seeking to take back Helen, once the wife of Menelaus but stolen by Paris, son of Priam, king of Troy. Unable to breach the walls and unwilling to go home empty-handed, the Greeks have marauded throughout the land, plundering and looting. Surviving captives, especially women, were taken as slaves and property. Among these was beautiful Briseis, claimed by Achilles, greatest of the Greek warriors, and Chryseis, claimed by Agamemnon, brother to Menelaus and leader of the Greek expedition. But Chryseis’ father is priest to the god Apollo, who forces Agamemnon to give Chryseis back. Feeling cheated, Agamemnon in turn requires Achilles to hand Briseis over to him.

Enraged by this insult, Achilles withdraws from the fight. Meanwhile, the war continues. Death after death after death after death. The Olympian gods conspire and argue. Achilles’ beloved best friend Patroclus puts on Achilles’ armor in an attempt to inspire the Greeks and to intimidate the Trojans. But the Trojan’s greatest warrior, Hector, son of Priam and brother to Paris, slays Patroclus.

Now Achilles’ endless wrath has a new target. He goes on a rampage, making the prior warfare look like a playground argument. He chokes the river Scamander with bodies. At last he faces Hector and kills him. This does not sate Achilles’ fury; he drags Hector’s body back and forth across the plain of Troy, in plain sight of Hector’s horrified family.

Priam goes in the dead of night to beg Achilles for the body of his son. Commanded by Zeus, and having realized the futility of war, Achilles agrees, and the Iliad ends with Hector’s funeral.

The Iliad is not easy for modern readers of the English language. It is a long poem translated from an ancient language fond of convoluted metaphors. The heavy use of adjectives—“white-armed Hera” (which signaled that she was an aristocratic woman who stayed in the dark of her home and sent slaves in her place to the sun-drenched markets), “swift-footed Achilles,” “long-haired Greeks,” and so on—is at odds with our experience of modern English: stripped down and wary of too many adjectives. The Iliad has many, many characters, most of whom are named mere moments before being slaughtered. Only three characters—Hector, Zeus, and of course Achilles—are explored at any length, and even they are rather flat. Women exist only as furniture and targets of sexual assault. (At one point Nestor, the oldest and allegedly the wisest of the Greeks, states explicitly they need to rape more Trojan women. Old King Priam of Troy, otherwise a sympathetic character, boasts of a hundred offspring not only from his wife but from his household, implying that any woman within reach was fair game for impregnation.) Even the goddesses, aside from Athena, are for the most part simpering.

These were of course the conventions of bronze age Greece. I don’t think Homer should have written his poem with the mores of three thousand years in the future in mind. Instead, I am explicating the challenges in reading such a strange and foreign poem, to say nothing of translating it for a modern audience. In that, Emily Wilson has done a fantastically admirable job.

Perhaps the biggest challenge, however, is the endless slaughter. Even to us living in an era of bloody, R-rated superhero and horror movies and video games, the death toll is staggering. Most kills are described in gory detail, how the spear or blade entered the victim (surprisingly often near the male nipple, whether an obvious target or eroticizing violence I am not sure) and a catalog of the fluids and organs spilling forth. Death is endless, and sickening, and numbing.

As an aside, let me say that I think the Odyssey is much more readable for a modern audience, especially Wilson’s supple translation. Odysseus is a rogue and a cad, but a charming one with a silver tongue. There is still violence and death, especially at the end where Odysseus and son Telemachus team up to murder Penelope’s suitors as well as a dozen ‘traitorous’ household women, though as slaves it’s not clear what choices they had. But Odysseus would generally rather talk than fight his way out of a conflict (though he is a skilled killer), and his fantastical adventures capture the imagination. Women and servants, who are mostly voiceless if not erased in the Iliad, leap to life in the Odyssey, even if their lives still revolve around Odysseus’ needs. In particular Penelope, while still shackled by her society’s codes, nonetheless shows herself as crafty as her husband; she is the only person in all of Homer who outwits the quick-minded Odysseus.

While I have been arguing that the Iliad reads as an alien text for modern audiences, there is a lens through which Homer prefigures modern techniques.

While on one hand, the Iliad is about aristocratic warriors seeking glory and immortal fame through strength of arms, it simultaneously undermines that narrative. The central characters of the Iliad are awful: petty, grasping, self-centered, and importantly unable to control their emotions. The first Greek word of the poem is menin: rage or wrath. Achilles is completely driven by wrath. First, he withholds his arms and allows his compatriots to die at the hands of the Trojans. Later, when his beloved friend Patroclus is killed, he slaughters the Trojans in such numbers the bodies choke the river Scamander. Even in the last book, when Achilles allows Priam to claim the body of his dead son Hector, Achilles warns the old man not to do anything that would trigger him into lashing out and killing Priam; although aware it would violate a divine mandate, Achilles sees himself as helpless to stopper his own emotions. From beginning to end, Achilles is slave to his rage.

Almost no one comes away looking good. The leader Agamemnon is shockingly small-minded and quick to take slight. In the funeral games meant to honor dead Patroclus, the competing Greeks whine and snipe and accuse each other of cheating. The chief god Zeus is a thuggish autocrat. Achilles himself is at heart a narcissist: he claims to love Patroclus as no other, but Patroclus’ shade has to beg him to hurry up and bury him so he is no longer trapped in agonizing limbo.

Today we are used to protagonists with unpalatable traits, and tales such as Watchmen or The Boys delve deep into the darkness of so-called heroes. Such stories are proclaimed as fresh takes, but, reading the Iliad, one sees the seeds of such internal contradictions have existed for thousands of years.

There is a fancy postmodernist literary term for this: deconstruction. Postmodernism was once viewed as dangerous cultural anarchy, but is now mostly spent: when I ask current college student if they’ve heard of it, they shrug. A key postmodernist concept is that while readers try to ‘construct’ a coherent theme from a narrative—love will triumph, power always corrupts, vengeance will self-destruct—deconstruction is the task to show that a text, any text, is not wholly consistent but rather contradictory, making all Grand Themes unstable. This has been mocked as suggesting the postmodernists believe nothing means anything (an impression not helped by postmodernism’s fondness for verbal wordplay, veering close to gobbledygook).

Aside from theoretical musings, deconstruction is a powerful narrative technique: putting forward a surface theme while simultaneously questioning it. The movie version of Starship Troopers is a classic example: like the Iliad, on the surface it is the story of brave young men and women fighting to keep humankind safe from mindless bugs, but the fascist symbols and Nazi-adjacent dress of the world government suggests humans themselves are not so innocent. George R. R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire series, and the subsequent HBO phenomenon Game of Thrones, deconstructs the romance of heroic fantasy through the shocking deaths of many would-be protagonists. (I believe the inherent difficulty of pulling off such deconstruction at length may be why Martin has all but abandoned his books, and why HBO reverted back to more teleological tropes to reach a conclusion.)

But none of this is new. Homer sang of famous Greek heroes who fought for glory, and yet in the details they were less than heroic. In the Iliad Achilles is well aware that despite his prowess he will soon die, and in the Odyssey, Achilles’ shade admits that a glorious death is not worth it. The Iliad is a tragedy: the purported heroes are but puppets for ridiculously flawed gods, as well as being at the mercy of their own raging emotions. Perhaps this is why the Iliad has rung out through the millenia: after it ends, one does not have the simple sense of ‘the good guys won,’ but rather the deeply uncomfortable—and memorable—feeling that everyone in it made terrible and fatal mistakes.

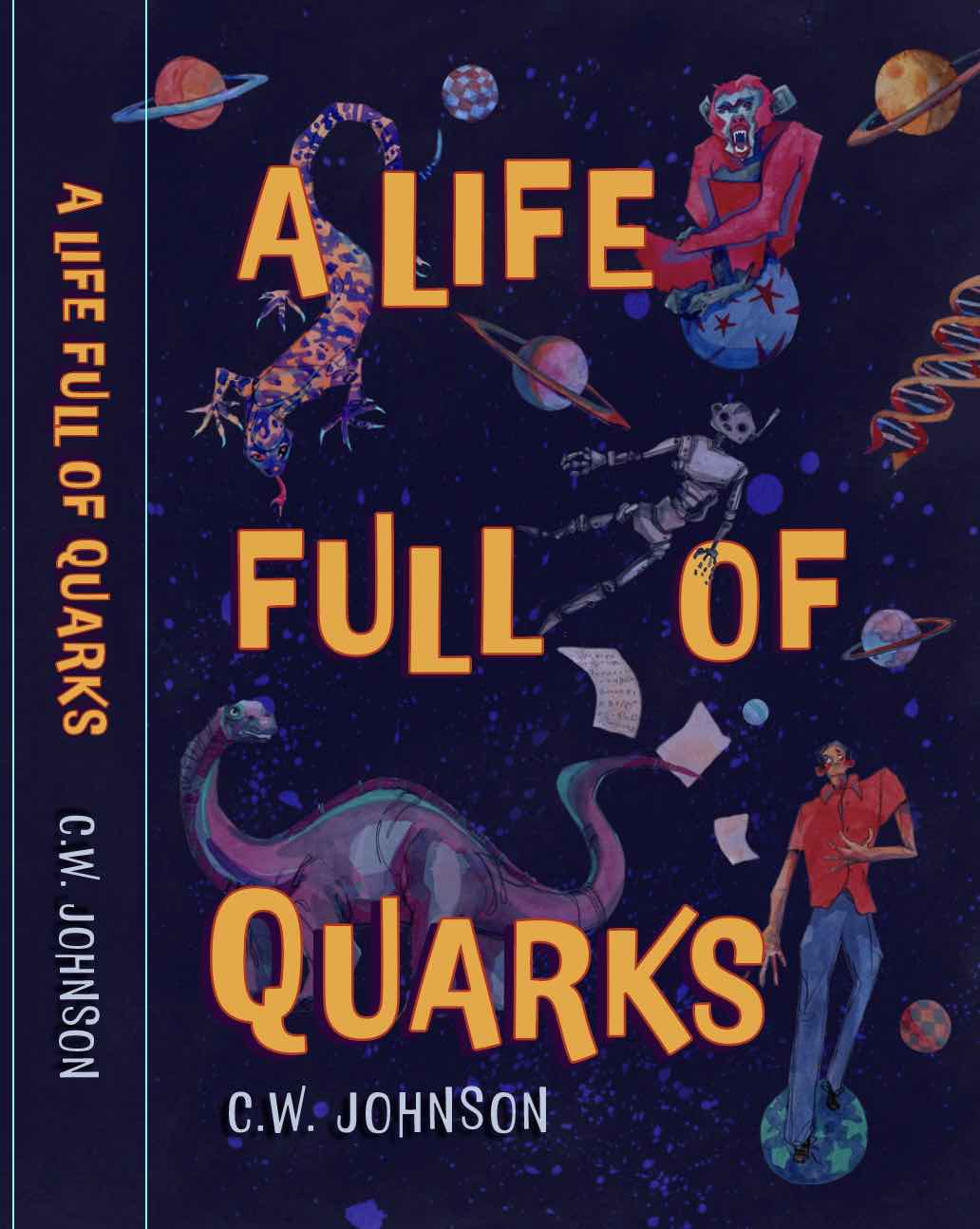

I should note that the final chapter of A Life Full of Quarks is titled “Postmodern Love.”

Final word: I make no claim to novel insights. I’m sure my classicist friends and colleagues (to say nothing of Greek friends who grew up with much deeper and more nuanced readings of Homer) would make easy hay of my essay. This is only my response, my personal review if you like, to my recent reading of the Iliad.