My story in self-publishing, part II: Publication

I had written, and rewritten, and edited and polished my novel. Now it was time to move towards actual publication.

Prior to hiring the developmental editor I had sent out inquiries to a handful of agents, but then felt it was likely hopeless. (I had also sent a complete draft to an insightful friend who runs a small press, but she declined to take it.) The developmental editor encouraged me to try more agents anyway, so I did my research and sent out query letters to eighty-four agents, most of whom I found through duotrope.com. I had originally planned for one hundred agents, but by the time I got to eighty-four I was having trouble finding agents who might be interested in my novel. (Most agents who are open to submissions will give authors an idea of the kind of book they are looking for.) Only about two-thirds of the agents replied, most with boilerplate letters. One did ask for the entire novel, but then declined. I don’t blame the agents; they get hundreds of submissions and it’s very hard to wade through those submissions to decide in which novel to invest significant time and energy.

So I decided to self-publish. It used to be that self-publishing a novel was severely looked down upon, the worst kind of vanity. Today, with advances in technology, the shrinking of the traditional publishing gatekeepers, and the explosion of, I guess, literacy, or the desire to speak with one’s own voice, self-publishing no longer has the odor of rotten meat.

To simply throw up a manuscript on Amazon turns out to be rather easy. If you want more control, and/or have more ambition, publishing can require more steps.

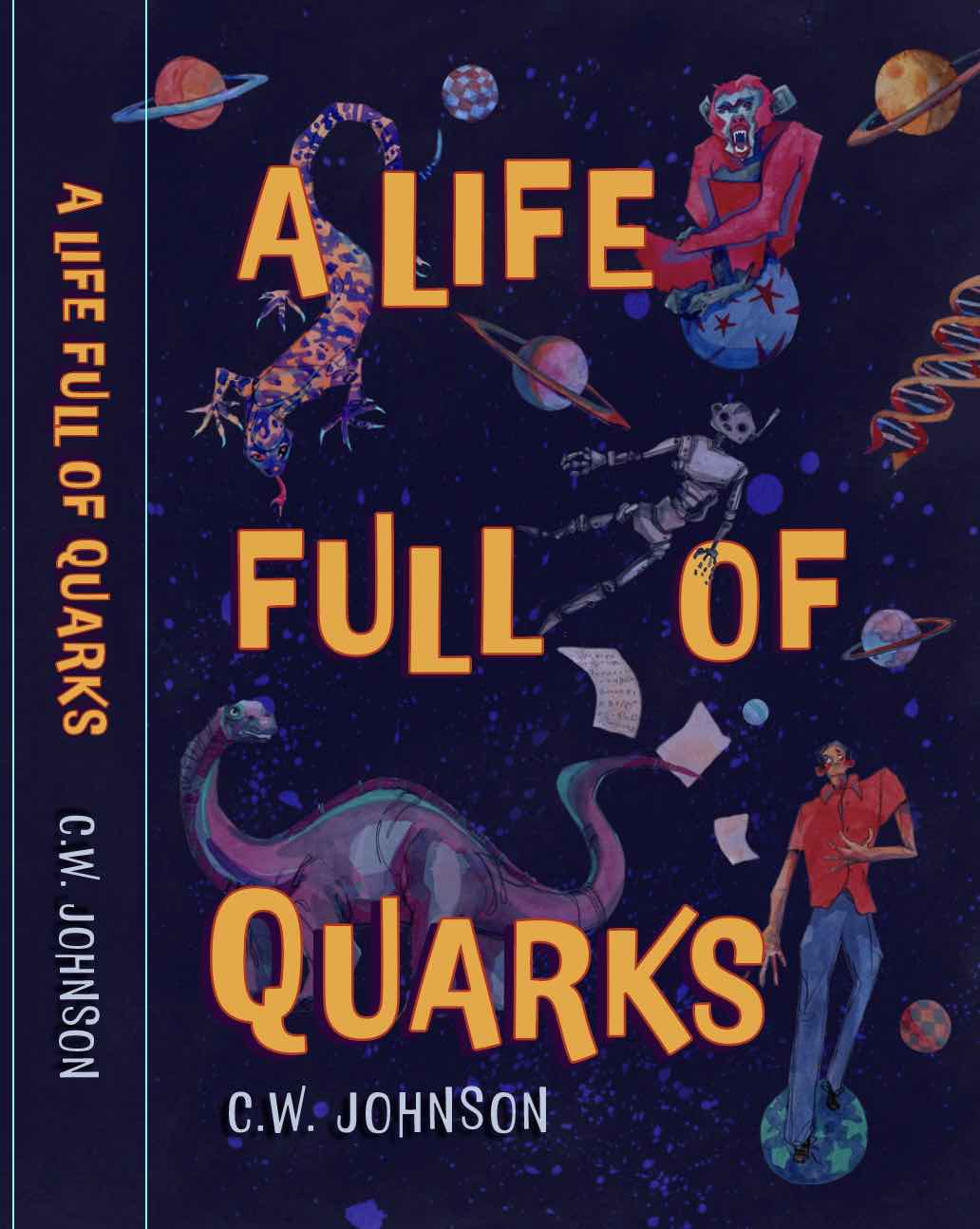

I needed a cover, and I needed to typeset the text. There are huge resources for covers. Looking at much of the cover art, I felt it tended to blur together into a sameness after a while. However, on reedsy.com I found an artist, Olive Reekie, who took her inspiration from German expressionism, and whose work significantly stood out from the rest. I hired her and, after a few small tweaks, was very happy with the result. (You can see the art on this website, and can follow her on Instagram: @olivereekie.)

As with everything else in self-publishing, there are a wide variety of formatting tools, from the free and nearly automatic to the expensive with a steep learning curve. The free tools work, but have a fairly rigid format with few options. I settled on atticus.io, an online tool that has a modest cost and is reasonably flexible without having to master a whole new scripting language.

Once the book was typeset, I could have hired a proofreader, which is a different task from copy-editor. Having already spent more money than I was likely to ever earn back, I decided to risk that copy-editing would have caught most mistakes. I did proofread the typeset version myself, and found a few clunky wordings that I fixed.

Now I had a cover and a typeset file of my manuscript, both in pdf format for print editions and in epub format for Kindle and other e-books.

Even though most self-published books only sell a few hundred copies, I decided to take this as a serious business. Therefore I went down to the county clerk’s office and registered myself with a DBA (Doing Business As), Baryon Dreams Press. The process was really quite easy and the clerk who helped me very friendly. (It was his first day on the job, so it was a new experience for both of us.) To formally finish the process, I had to make public my new DBA, and take out an ad in a local paper for four weeks. Again, the person at the small local paper was very helpful and the cost was minimal. In order to have a clear separation between my personal finances I applied for an EIN, an Employer Identification Number, which I can use instead of my personal social security number; once more, the IRS made this extremely simple. The last step, which I have yet to do, will be to set up a business banking account, probably at the bank where my wife does the banking for her small business. (UPDATE: The bank was surprisingly incompetent, unable to use the correct e-mail address, so I will look for a different bank.)

Every book published needs an identification number, an ISBN for physical books, and for e-books either an ISBN or Amazon’s own personal id number. Some vendors will provide/sell you an ISBN, but if you are a bit controlling like me, ISBNs can be purchased in the US through Bowker publishing services (www.myidentifiers.com ; interestingly, while bowker.com points correctly, someone is squatting on bowkers.com, a lesson for us all). A single ISBN is quite expensive, but bought in bulk, say 10, is much more reasonable. Books also need bar codes, which you can generate but most if not all vendors will provide those for free.

The next steps were to set up accounts on various vendors and upload my manuscript. By vendor I mean companies like Amazon that will sell books for you. It’s possible to sell books directly from a personal website, but of course the major vendors get more traffic.

I first set up an account on Amazon KDP which turned out to be pretty easy. I had to tweak my cover a bit, to make sure the title on the spine was correctly aligned, but Amazon provided templates that made this straightforward. Once everyone was uploaded I was able to order physical proof copies, and a few days later had my book in my hand! It was quite heady.

Other sites were not as easy. At the time of this writing I have set up my book on Barnes & Noble and IngramSpark, and am in the process for selling it through Apple. None of them were as easy as Amazon.

(I am a bit wary of Amazon’s overarching dominance of the market on, well, everything, but I have to say, they do work hard to make it easy. I also shop on Amazon more than other sites simply because it reduces the number of places I have to share my credit card information.)

IngramSpark is a major printer of books, and if an independent bookstore were to carry a self-published book, they would likely order it through IngramSpark. Nonetheless the upload process on IngramSpark was much fussier than for Amazon, and I kept getting error messages with minimal explanation. For example, it told me I had uploaded the cover image for my e-book with the wrong format, and after multiple tries uploading in the “correct” format, I finally guessed that the cover image embedded in the epub file itself was in the wrong format. In addition, I kept being told there was something wrong with the .pdf file for the print version. Eventually, by scouring internet comment boards, I learned that IngramSpark required a very specific .pdf format, the pdf/X format. This information is available on IngramSpark, but it is deeply buried. Also, only certainly image processing tools (i.e., not the free ones) will generate the pdf/X format. Fortunately my wife for her business had one I could use.

Even after all the files were properly formatted and uploaded, I got yet another mysterious message about the book having never been put into production. I finally had to contact IngramSpark support, and was told this was a new problem affecting multiple books. Several days later it was finally resolved, and my book approved for publication on IngramSpark.

(Another important issue with IngramSpark is book returns. Amazon, and I believe Barnes & Noble, are POD, print on demand, only. IngramSpark will sell cartons of physical books to physical bookstores, usually at a heavily discounted rate, i.e., out of the author’s profit. But the bookstore profit margin is paper thin, so physical bookstores want to be able to return unsold books for a full refund. At IngramSpark, that refund comes out of, you guessed it, the author’s pocket. You can decline returns, but that will for all practical purposes eliminate any small bookstores selling your book; you can choose returns that are destroyed; or you can choose for those returns to be sent to you so that you might resell them. There are lots of arguments on the internet pro and con about those choices. Right now I am planning to allow for returns for the first six months, so that local bookstores near me might carry my book. The danger is that what little profit I am making could be swallowed up by return charges. Luckily I am not planning for this to keep me fed in retirement.)

Self-publishing on Barnes and Noble was in-between: not nearly as painless as Amazon, but also not as hair-pulling-out as IngramSpark.

Currently I am working on setting up my book to be sold through Apple. For this I needed to set up an “itunes connect” account. When I tried to do this, however, I was told my base itunes account did not have a valid credit card associated with it, even though I have used that account and that card to purchase Apple products multiple times. Internet message boards were not helpful, and suggested I would have to call Apple support. After a few days, however, I tried once more and Apple agreed my credit card was valid and I could set up an itunes connect account.

There are people & organizations that will do all of this for you—for a larger cut of the money. Even at this level of going through vendors, Amazon, B&N, IngramSpark, etc., take a chunk of money, typically 30% after any production costs.

Now the book appears online, available for sale after September 24, 2024, a date I choose to give me time to coordinate everything.

Alas, my work is not done. There is still publicity and marketing, including setting up this website. That will be the next chapter.